How Consensus Can Impede Scientific Progress

/As I wrote several years ago (see here), a commonly misunderstood concept in science is the role of consensus. A scientific consensus is built by the slow accumulation of unambiguous pieces of empirical evidence, until the collective evidence is strong enough to become a theory.

Scientific consensus, however, is never reached by taking a poll of scientists. And a consensus isn’t necessarily the last word. A consensus, whether newly proposed or well-established, can be wrong. Failure to recognize this possibility has often held up progress in science.

A recent example comes from the field of archaeology. Throughout the 20th century, the predominant hypothesis was that humans first reached the Americas at the end of the last ice age about 13,000 years ago, when melting ice created a now submerged landmass known as Beringia, shown in the figure below. Asian hunters crossed from Siberia to Alaska, these so-called Clovis people (named after a unique type of spear point they used) subsequently migrating south along the edges of melting ice sheets to warmer climes.

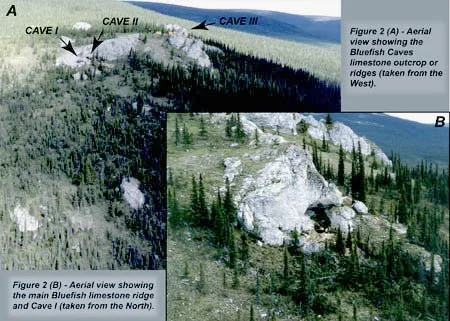

But despite evidence that the Clovis were not the first arrivals in the Americas, archaeologists who disputed the conventional wisdom were all but ignored and the sites they investigated were disregarded. Prominent among these naysayers was Canadian archaeologist Jacques Cinq-Mars, who carried out excavations at the Bluefish Caves in northwestern Yukon from 1977 to 1987.

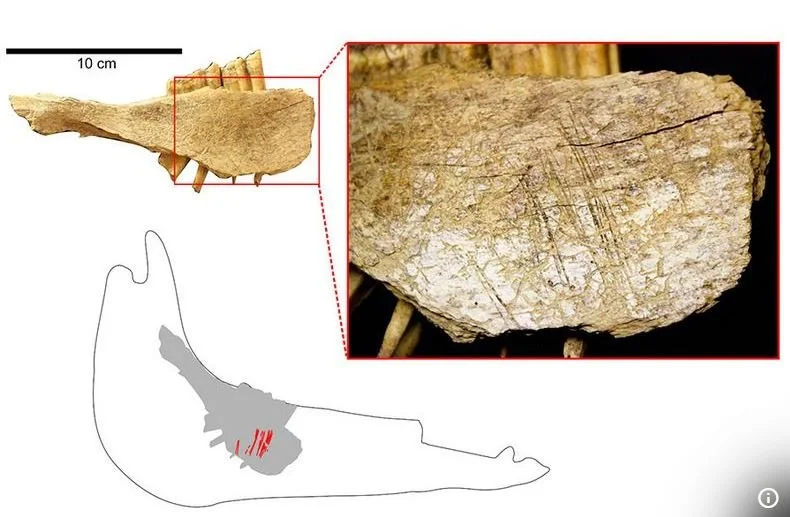

Cinq-Mars and his team made an important discovery – bones of horses and woolly mammoths that exhibited cut marks from human butchering and toolmaking. Depicted on the left is a fragment from a horse’s jawbone showing deep thin cuts with a V-shaped profile, typical of butchery to remove muscle. Even more remarkably, radiocarbon testing dated the oldest finds to around 24,000 years ago, thousands of years before the Clovis people were thought to have been in the vicinity.

Reinforcement for Cinq-Mars’ new hypothesis about the first inhabitants of both North (and South) America came from another archaeological study in Washington state, where evidence was found for slaughtering and butchering of mastodons using all-purpose stone tools that resembled Exacto blades, during the same time period as the Bluefish Caves discoveries.

Another significant piece of evidence against the Clovis-first hypothesis was the discovery in Chile of “stone tools, remains of a large hide-covered shelter that may have housed 30 people, communal hearths, chunks of mastodon meat, and three human footprints,” the oldest of which was dated to 14,500 years in the past – again, before the Clovis even crossed Beringia.

Nevertheless, Cinq-Mars’ discovery was met with often acrimonious skepticism at the time, because the renegade archaeologist had dared to contest the prevailing consensus. His competence and sanity were constantly ridiculed and his conference presentations laughed at, experiences that he likened to questioning by the Inquisition. Eventually, even funding for his fieldwork dried up. Only now, some 40 years later, has the Clovis-first model become outmoded among most archaeologists and Cinq-Mars finally vindicated.

These ad hominem attacks on Cinq-Mars were no more virulent, however, than those directed earlier in the century at Alfred Wegener, the German meteorologist who proposed the revolutionary theory of continental drift.

Wegener was vehemently criticized by his peers because his theory threatened the geology establishment, which clung to the old consensus of rigidly fixed continents. One critic harshly dismissed his hypothesis as “footloose,” and geologists scorned what they called Wegener’s “delirious ravings” and other symptoms of “moving crust disease.” It wasn’t for almost 60 years that continental drift theory was accepted by mainstream geologists, after compelling evidence for the theory emerged.

These are not isolated examples in scientific history. Another, from the 19th century in the field of medicine, was the discovery of the now unquestioned importance of handwashing to prevent infection in hospitals. At that time, up to 10% of women who had their babies delivered by obstetricians used to die from so-called childbed fever shortly after childbirth. In deliveries performed by midwives or at home, the death rate was several times lower.

A combative Hungarian obstetrician named Ignaz Semmelweis came up with the brilliant realization that hospital obstetricians weren’t washing their hands after carrying out barehanded autopsies on the pus-ridden bodies of women who had suffered an anguished death from the same disease only the day before. Once Semmelweis proposed that doctors wash their hands vigorously in a chlorinated lime solution after conducting autopsies, the mortality rate in obstetric wards plummeted.

But the discovery was widely rejected by the medical establishment of the day, whose consensus about disease was that it came from an imbalance in the four bodily humors of Hippocratic medical theory. Not until 20 years later, after Semmelweis had been beaten to death in an asylum, was his infection hypothesis vindicated by the newly accepted germ theory of disease.

I’ve documented further examples of scientific progress being impeded by a mistaken mainstream consensus here.

Next: Ice Sheet Update (2): Greenland Ice Sheet Loss Slows Down