Targeting Farmers for Livestock Greenhouse Gas Emissions Is Misguided

/Farmers in many countries are increasingly coming under attack over their livestock herds. Ireland’s government is contemplating culling the country’s cattle herds by 200,000 cows to cut back on methane (CH4) emissions; the Dutch government plans to buy out livestock farmers to lower emissions of CH4 and nitrous oxide (N2O) from cow manure; and New Zealand is close to taxing CH4 from cow burps.

But all these measures, and those proposed in other countries, are misguided and shortsighted – for multiple reasons.

The thrust behind the intended clampdown on the farming community is the estimated 11-17% of current greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture worldwide, which contribute to global warming. Agricultural CH4, mainly from ruminant animals, accounted for approximately 4% of total greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S. in 2021, according to the EPA (Environmental Protection Agency), while N2O accounted for another 5%.

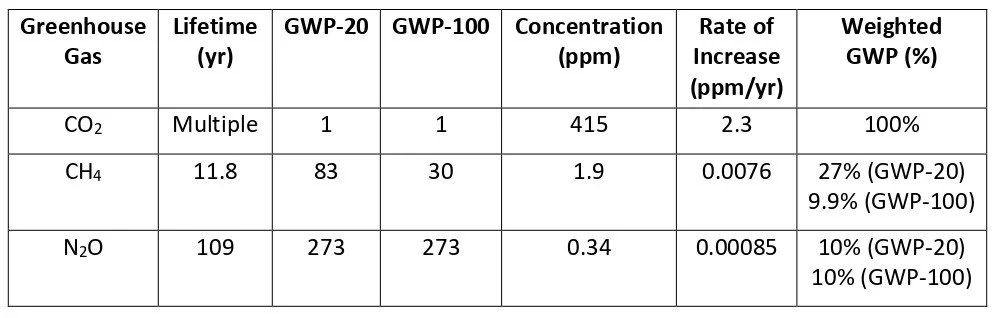

The actual warming produced by these two greenhouse gases depends on their so-called “global warming potential,” a quantity determined by three factors: how efficiently the gas absorbs heat, its lifetime in the atmosphere, and its atmospheric concentration. The following table illustrates these factors for CO2, CH4 and N2O, together with their comparative warming effects.

The conventional global warming potential (GWP) is a dimensionless metric, in which the GWP per molecule of a particular greenhouse gas is normalized to that of CO2; the GWP takes into account the atmospheric lifetime of the gas. The table shows both GWP-20 and GWP-100, the warming potentials calculated over a 20-year and 100-year time horizon, respectively.

The final column shows what I call weighted GWP values, as percentages of the CO2 value, calculated by multiplying the conventional GWP by the ratio of the rate of concentration increase for that gas to that of CO2. The weighted GWP indicates how much warming CH4 or N2O causes relative to CO2.

Over a 100-year time span, you can see that both CH4 and N2O exert essentially the same warming influence, at 10% of CO2 warming. But over a 20-year interval, CH4 has a stronger warming effect than N2O, at 27% of CO2 warming, because of its shorter atmospheric lifetime which boosts the conventional GWP value from 30 (over 100 years) to 83.

However, the actual global temperature increase from CH4 and N2O – concern over which is the basis for legislation targeting the world’s farmers – is small. Over a 20-year period, the combined contribution of these two gases is approximately 0.075 degrees Celsius (0.14 degrees Fahrenheit), assuming that all current warming comes from CO2, CH4 and N2O combined, and using a value of 0.14 degrees Celsius (0.25 degrees Fahrenheit) per decade for the current warming rate.

But, as I’ve stated in many previous posts, at least some current warming is likely to be from natural sources, not greenhouse gases. So the estimated 20-year temperature rise of 0.075 degrees Celsius (0.14 degrees Fahrenheit) is probably an overestimate. The corresponding number over 100 years, also an overestimate, is 0.23 degrees Celsius (0.41 degrees Fahrenheit).

Do such small, or even smaller, gains in temperature justify the shutting down of agriculture? Farmers around the globe certainly don’t think so, and for good reason.

First, CH4 from ruminant animals such as cows, sheep and goats accounts for only 4% of U.S. greenhouse emissions as noted above, compared with 29% from transportation, for example. And our giving up eating meat and dairy products would have little impact on global temperatures. Removing all livestock and poultry from the U.S. food system would only reduce global greenhouse gas emissions by 0.36%, a study has found.

Other studies have shown that the elimination of all livestock from U.S. farms would leave our diets deficient in vital nutrients, including high-quality protein, iron and vitamin B12 that meat provides, says the Iowa Farm Bureau.

Furthermore, as agricultural advocate Kacy Atkinson argues, the methane that cattle burp out during rumination breaks down in 10 to 15 years into CO2 and water. The grasses that cattle graze on absorb that CO2, and the carbon gets sequestered in the soil through the grasses’ roots.

Apart from cow manure management, the largest source of N2O emissions worldwide is the application of nitrogenous fertilizers to boost crop production. Greatly increased use of nitrogen fertilizers is the main reason for massive increases in crop yields since 1961, part of the so-called green revolution in agriculture.

The figure below shows U.S. crop yields relative to yields in 1866 for corn, wheat, barley, grass hay, oats and rye. The blue dashed curve is the annual agricultural usage of nitrogen fertilizer in megatonnes (Tg). The strong correlation with crop yields is obvious.

Restricting fertilizer use would severely impact the world’s food supply. Sri Lanka’s ill-conceived 2022 ban of nitrogenous fertilizer (and pesticide) imports caused a 30% drop in rice production, resulting in widespread hunger and economic turmoil – a cautionary tale for any efforts to extend N2O reduction measures from livestock to crops.

Next: No Evidence That Today’s El Niños Are Any Stronger than in the Past