No Evidence That Climate Change Is Accelerating Sea Level Rise

/Malé, Maldives Capital City

By far the most publicized phenomenon cited as evidence for human-induced climate change is rising sea levels, with the media regularly trumpeting the latest prediction of the oceans flooding or submerging cities in the decades to come. Nothing instills as much fear in low-lying coastal communities as the prospect of losing one’s dwelling to a hurricane storm surge or even slowly encroaching seawater. Island nations such as the Maldives in the Indian Ocean and Tuvalu in the Pacific are convinced their tropical paradises are about to disappear beneath the waves.

There’s no doubt that the average global sea level has been increasing ever since the world started to warm after the Little Ice Age ended around 1850. But there’s no reliable scientific evidence that the rate of rise is accelerating, or that the rise is associated with any human contribution to global warming.

A comprehensive 2018 report on sea level and climate change by Judith Curry, a respected climate scientist and global warming skeptic, emphasizes the complexity of both measuring and trying to understand recent sea level rise. Because of the switch in 1993 from tide gauges to satellite altimetry as the principal method of measurement, the precise magnitude of sea level rise as well as projections for the future are uncertain.

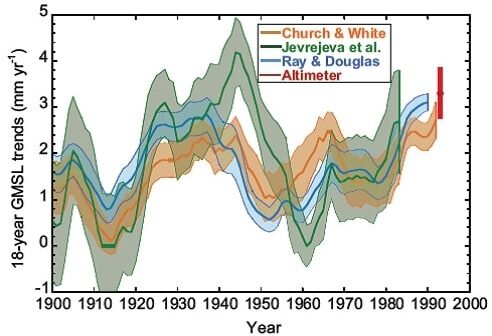

According to both Curry and the UN’s IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), the average global rate of sea level rise from 1901 to 2010 was 1.7 mm (about 1/16th of an inch) per year. In the latter part of that period from 1993 onward, the rate of rise was 3.2 mm per year, almost double the average rate – though this estimate is considered too high by some experts. But, while the sudden jump may seem surprising and indicative of acceleration, the fact is that the globally averaged sea level fluctuates considerably over time. This is illustrated in the IPCC’s figure below, which shows estimates from tide gauge data of the rate of rise from 1900 to 1993.

It’s clear that the rate of rise was much higher than its 20th century average during the 30 years from 1920 to 1950, and much lower than the average from 1910 to 1920 and again from 1955 to 1980. Strong regional differences exist too. Actual rates of sea level rise range from negative in Stockholm, corresponding to a falling sea level, as that region continues to rebound after melting of the last ice age’s heavy ice sheet, to positive rates three times higher than average in the western Pacific Ocean.

The regional variation is evident in the next figure, showing the average rate of sea level rise across the globe, measured by satellite, between 1993 and 2014.

You can see that during this period sea levels increased fastest in the western Pacific as just noted, and in the southern Indian and Atlantic Oceans. At the same time, the sea level fell near the west coast of North America and in the Southern Ocean near Antarctica.

The reasons for such a jumbled picture are several. Because water expands and occupies more volume as it gets warmer, higher ocean temperatures raise sea levels. Yet the seafloor is not static and can sink under the weight of the extra water in the ocean basin that comes from melting glaciers and ice caps, and can be altered by underwater volcanic eruptions. Land surfaces can also sink (as well as rebound), as a result of groundwater depletion in arid regions or landfilling in coastal wetlands. For example, about 50% of the much hyped worsening of tidal flooding in Miami Beach, Florida is due to sinking of reclaimed swampland.

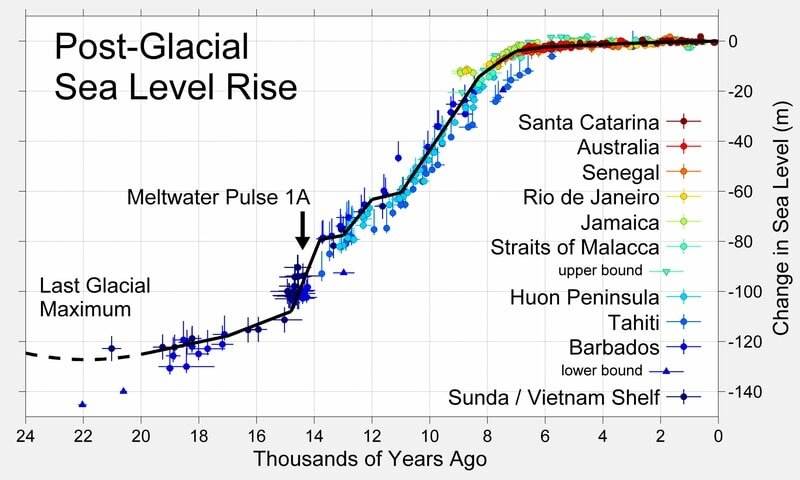

Historically, sea levels have been both lower and higher in the past than at present. Since the end of the last ice age, the average level has risen about 120 meters (400 feet), as depicted in the following figure. After it reached a peak in at least some regions about 6,000 years ago, however, the sea level has changed relatively little, even when industrialization began boosting atmospheric CO2. Over the 20th century, the worldwide average rise was about 15-18 cm (6-7 inches).

That the concerns of islanders are unwarranted despite rising seas is borne out by recent studies revealing that low-lying coral reef islands in the Pacific are actually growing in size by as much as 30% per century, and not shrinking. The growth is due to a combination of coral debris buildup, land reclamation and sedimentation. Another study found that the Maldives -- the world's lowest country -- formed when sea levels were even higher than they are today. Studies such as these belie the popular claim that islanders will become “climate refugees,” forced to leave their homes as sea levels rise.

Next: Shrinking Sea Ice: Evaluation of the Evidence