Retractions of Scientific Papers Are Skyrocketing

/A trend that bodes ill for the future of scientific publishing, and another signal that science is under attack, is the soaring number of research papers being retracted. According to a recent report in Nature magazine, over 10,000 retractions were issued for scientific papers in 2023.

Although more than 8,000 of these were sham articles from a single publisher, Hindawi, all the evidence shows that retractions are rising more rapidly than the research paper growth rate. The two figures below depict the yearly number of retractions since 2013, and the retraction rate as a percentage of all scientific papers published from 2003 to 2022.

Clearly, there is cause for alarm as both the number of retractions and the retraction rate are accelerating. Nature’s analysis suggests that the retraction rate has more than trebled over the past decade to its present 0.2% or above. And the journal says the estimated total of about 50,000 retractions so far is only the tip of the iceberg of work that should be retracted.

An earlier report in 2012 by a trio of medical researchers reviewed 2,047 biomedical and life-science research articles retracted since 1977. They found that 43% of the retractions were attributable to fraud or suspected fraud, 14% to duplicate publication and 10% to plagiarism, with 21% withdrawn because of error. The researchers also discovered that retractions for fraud or suspected fraud as a percentage of total articles published have increased almost 10 times since 1975.

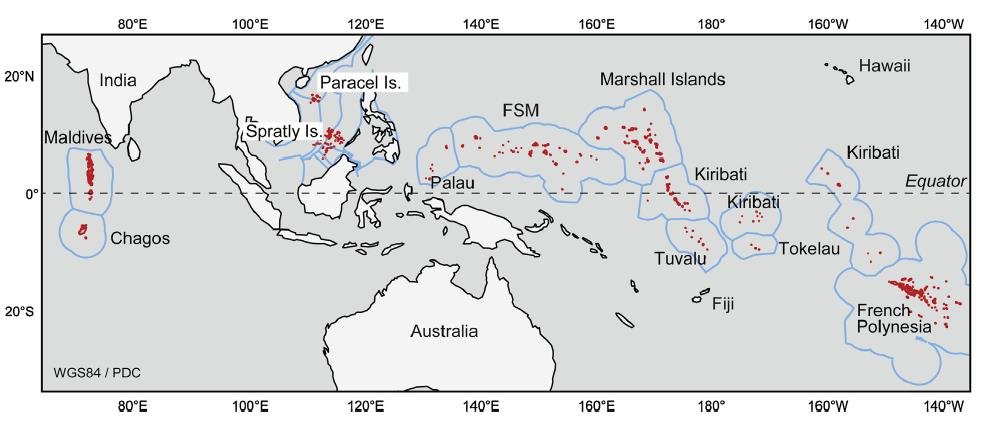

A recent example of fraud outside the biomedical area is the 2022 finding of the University of Delaware that star marine ecologist Danielle Dixson was guilty of research misconduct, for fabricating and falsifying research results in her work on fish behavior and coral reefs. As reported in Science magazine, the university subsequently sought retraction of three of Dixson’s papers.

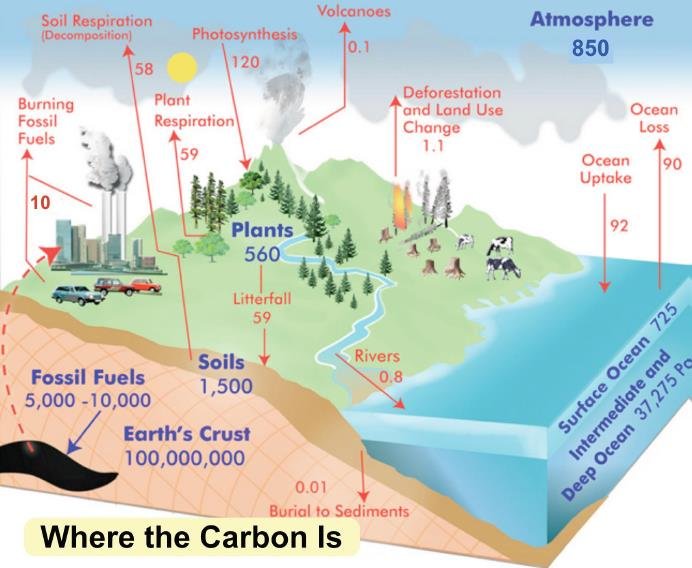

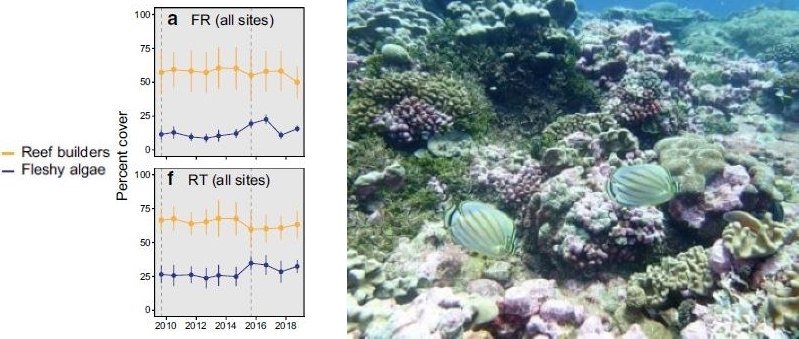

The misconduct involves studies by Dixson of the behavior of coral reef fish in slightly acidified seawater, in order to simulate the effect of ocean acidification caused by the absorption of up to 30% of human CO2 emissions. Dixson and Philip Munday, a former marine ecologist at James Cook University in Townsville, Australia, claimed that the extra CO2 causes reef fish to be attracted by chemical cues from predators, instead of avoiding them; to become hyperactive and disoriented; and to suffer loss of vision and hearing.

But, as I described in a 2021 blog post, a team of biological and environmental researchers led by Timothy Clark of Deakin University in Geelong, Australia debunked all these conclusions. Most damningly of all, the researchers found that the reported effects of ocean acidification on the behavior of coral reef fish were not reproducible.

The investigative panel at the University of Delaware endorsed Clark’s findings, saying it was “repeatedly struck by a serial pattern of sloppiness, poor recordkeeping, copying and pasting within spreadsheets, errors within many papers under investigation, and deviation from established animal ethics protocols.” The panel also took issue with the reported observation times for two of the studies, stating that the massive amounts of data could not have been collected in so short a time. Dixson has since been fired from the university.

Closely related to fraud is the reproducibility crisis – the vast number of peer-reviewed scientific studies that can’t be replicated in subsequent investigations and whose findings turn out to be false, like Dixson’s. In the field of cancer biology, for example, scientists at Amgen in California discovered in the early 2000s that an astonishing 89% of published results couldn’t be reproduced.

One of the reasons for the soaring number of retractions is the rapid growth of fake research papers churned out by so-called “paper mills.” Paper mills are shady businesses that sell bogus manuscripts and authorships to researchers who need journal publications to advance their careers. Another Nature report suggests that over the past two decades, more than 400,000 published research articles show strong textual similarities to known studies produced by paper mills; the rising trend is illustrated in the next figure.

German neuropsychologist Bernhard Sabel estimates that in medicine and neuroscience, as many as 11% of papers in 2020 were likely paper-mill products. University of Oxford psychologist and research-integrity sleuth Dorothy Bishop found signs of paper mill-activity last year in at least 10 journals from Hindawi, the publisher mentioned earlier.

Textual similarities are only one fingerprint of paper-mill publications. Others include suspicious e-mail addresses that don’t correspond to any of a paper’s authors; e-mail addresses from hospitals in China (because the issue is known to be so common there); manipulated images from other papers; twisted phrases that indicate efforts to avoid plagiarism detection; and duplicate submissions across journals.

Journals, fortunately, are starting to pay more attention to paper mills, revamping their review processes for example. They’re also being aided by an ever-growing army of paper-mill detectives such as Bishop.

Next: Exactly How Large Is the Urban Heat Island Effect in Global Warming?