Latest UN Climate Report Is More Hype than Science

/In its latest climate report, the UN’s IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) falls prey to the hype usually characteristic of alarmists who ignore the lack of empirical evidence for the climate change narrative of “unequivocal” human-caused global warming.

Past IPCC assessment reports have served as the voice of authority for climate science and, even among those who believe in man-made climate change, as a restraining influence – being hesitant in linking weather extremes to a warmer world, for instance. But all that has changed in its Sixth Assessment Report, which the UN Secretary-General has hysterically described as “code red for humanity.”

Among other claims trumpeted in the report is the statement that “Evidence of observed changes in extremes such as heat waves, heavy precipitation, droughts, and tropical cyclones, and, in particular, their attribution to human influence, has strengthened since [the previous report].” This is simply untrue and actually contrary to the evidence, with the exception of precipitation that tends to increase with global warming because of enhanced evaporation from tropical oceans, resulting in more water vapor in the atmosphere.

In other blog posts and a recent report, I’ve shown how there’s no scientific evidence that global warming triggers extreme weather, or even that weather extremes are becoming more frequent. Anomalous weather events, such as heat waves, hurricanes, floods, droughts and tornadoes, show no long-term trend over more than a century of reliable data.

As one example, the figure below shows how the average global area and intensity of drought remained unchanged on average from 1950 to 2019, even though the earth warmed by about 1.1 degrees Celsius (2.0 degrees Fahrenheit) over that interval. The drought area is the percentage of total global land area, excluding ice sheets and deserts, while the intensity is characterized by the self-calibrating Palmer Drought Severity Index, which measures both dryness and wetness and classifies events as “moderate,” “severe” or “extreme.”

Although the IPCC report claims, with high confidence, that “the frequency of concurrent heatwaves and droughts on the global scale” are increasing, the scientific evidence doesn’t support such a bold assertion. An accompanying statement that cold extremes have become less frequent and less severe is also blatantly incorrect.

Cold extremes are in fact on the rise, as I’ve discussed in previous blog posts (here and here). The IPCC’s sister UN agency, the WMO (World Meteorological Organization) does at least acknowledge the existence of cold weather extremes, but has no explanation for their origin nor their growing frequency. Cold extremes include prolonged cold spells, unusually heavy snowfalls and longer winter seasons. Why the IPCC should draw the wrong conclusion about them is puzzling.

In discussing the future climate, the IPCC makes use of five scenarios that project differing emissions of CO2 and other greenhouse gases. The scenarios start in 2015 and range from one that assumes very high emissions, with atmospheric CO2 doubling from its present level by 2050, to one assuming very low emissions, with CO2 declining to “net zero” by mid-century.

But, as pointed out by the University of Colorado’s Roger Pielke Jr., the estimates in the IPCC report are dominated by the highest emissions scenario. Pielke finds that this super-high emissions scenario accounts for 41.5% of all scenario mentions in the report, whereas the scenarios judged to be the most likely under current trends account for only a scant 18.4% of all mentions. The hype inherent in the report is obvious by comparing these percentages with the corresponding ones in the Fifth Assessment Report, which were 31.4% and 44.5%, respectively.

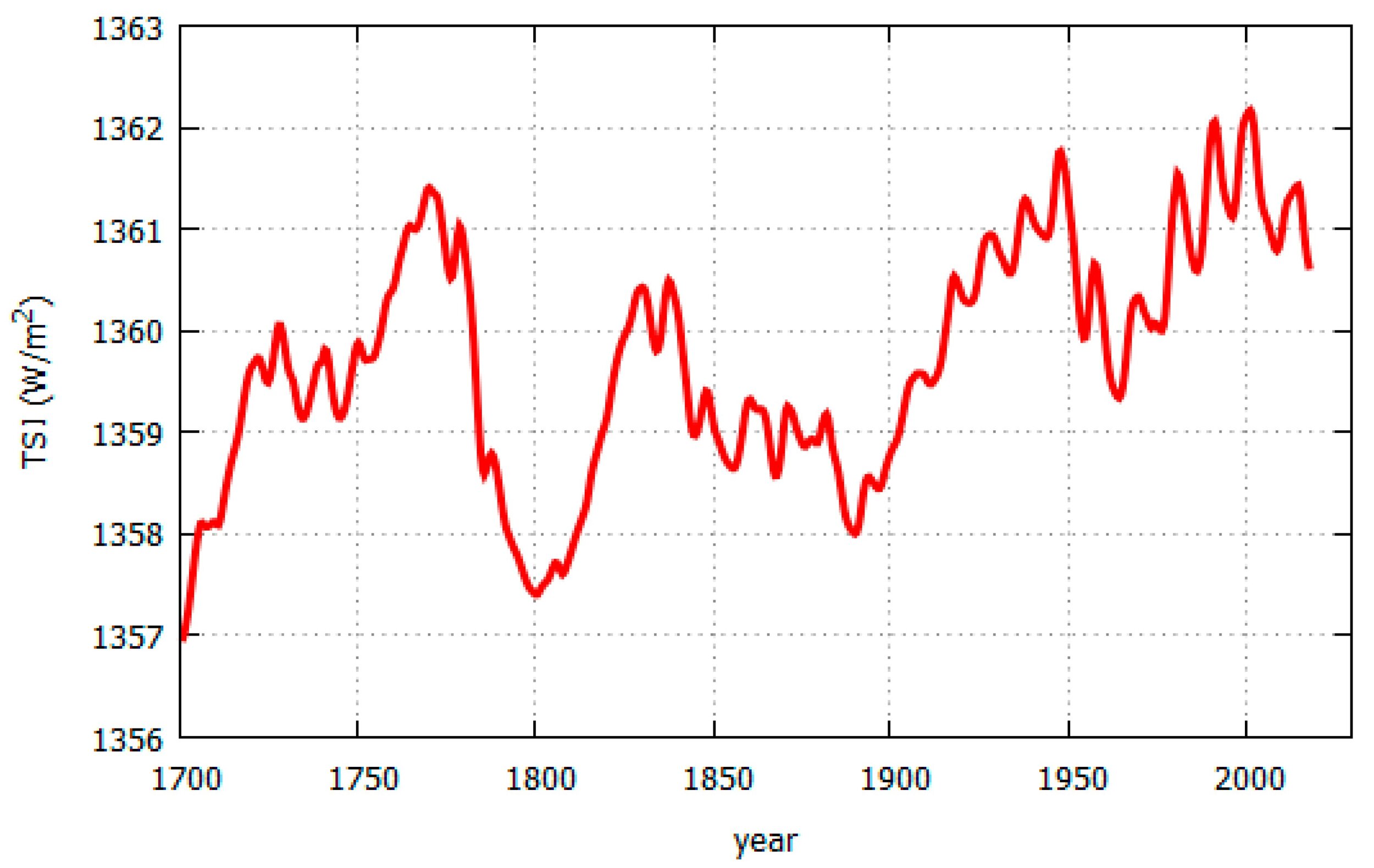

Not widely known is that the supposed linkage between climate change and human emissions of greenhouse gases, as well as the purported connection between global warming and weather extremes, both depend entirely on computer climate models. Only the models link climate change or extreme weather to human activity. The empirical evidence does not – it merely shows that the planet is warming, not what’s causing the warming.

A recent article in the mainstream scientific journal Science surprisingly drew attention to the shortcomings of climate models, weaknesses that have been emphasized for years by climate change skeptics. Apart from falsely linking global warming to CO2 emissions – because the models don’t include many types of natural variability – the models greatly exaggerate predicted temperatures, and can’t even reproduce the past climate accurately. As leading climate scientist Gavin Schmidt says, “You end up with numbers for even the near-term that are insanely scary—and wrong.”

The new IPCC report, with its prognostications of gloom and doom, should have paid more attention to its modelers. In making wrong claims about the present climate, and relying too heavily on high-emissions scenarios for future projections, the IPCC has strayed from the path of science.

Next: Weather Extremes: Hurricanes and Tornadoes Likely to Diminish in 2021