Was the Permian Extinction Caused by Global Warming or CO2 Starvation?

/Of all the mass extinctions in the earth’s distant past, by far the greatest and most drastic was the Permian Extinction, which occurred during the Permian between 300 and 250 million years ago. Also known as the Great Dying, the Permian Extinction killed off an estimated 57% of all biological families including rainforest flora, 81% of marine species and 70% of terrestrial vertebrate species that existed before the Permian’s last million years. What was the cause of this devastation?

The answer to that question is controversial among paleontologists. For many years, it has been thought the extinction was a result of ancient global warming. During Earth’s 4.5-billion-year history, the global average temperature has fluctuated wildly, from “hothouse” temperatures as much as 14 degrees Celsius (25 degrees Fahrenheit) above today’s level of about 14.8 degrees Celsius (27 degrees Fahrenheit), to “icehouse” temperatures 6 degrees Celsius (11 degrees Fahrenheit) below.

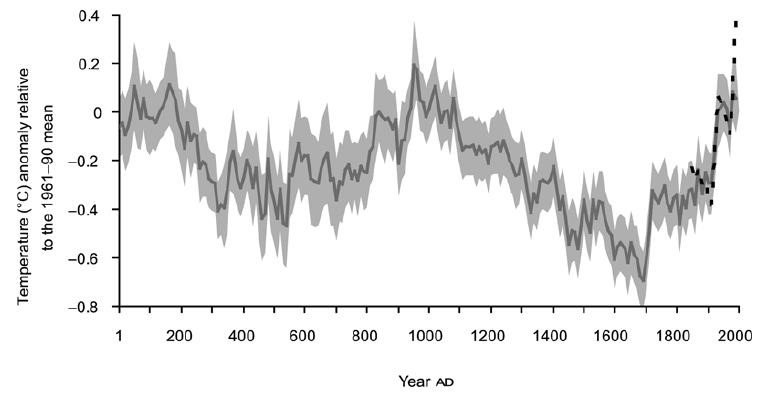

Hottest of all was a sudden temperature spike from icehouse conditions at the onset of the Permian to extreme hothouse temperatures at its end, as can be seen in the figure below. The figure is a 2021 estimate of ancient temperatures derived from oxygen isotopic measurements combined with lithologic climate indicators, such as coals, sedimentary rocks, minerals and glacial deposits. The barely visible time scale is in millions of years before the present.

The geological event responsible for this enormous surge in temperature is a massive volcanic eruption known as the Siberian Traps. The eruption lasted at least 1 million years and resulted in the outpouring of voluminous quantities of basaltic lava from rifts in West Siberia; the lava buried over 50% of Siberia in a blanket up to 6.5 km (4 miles) deep.

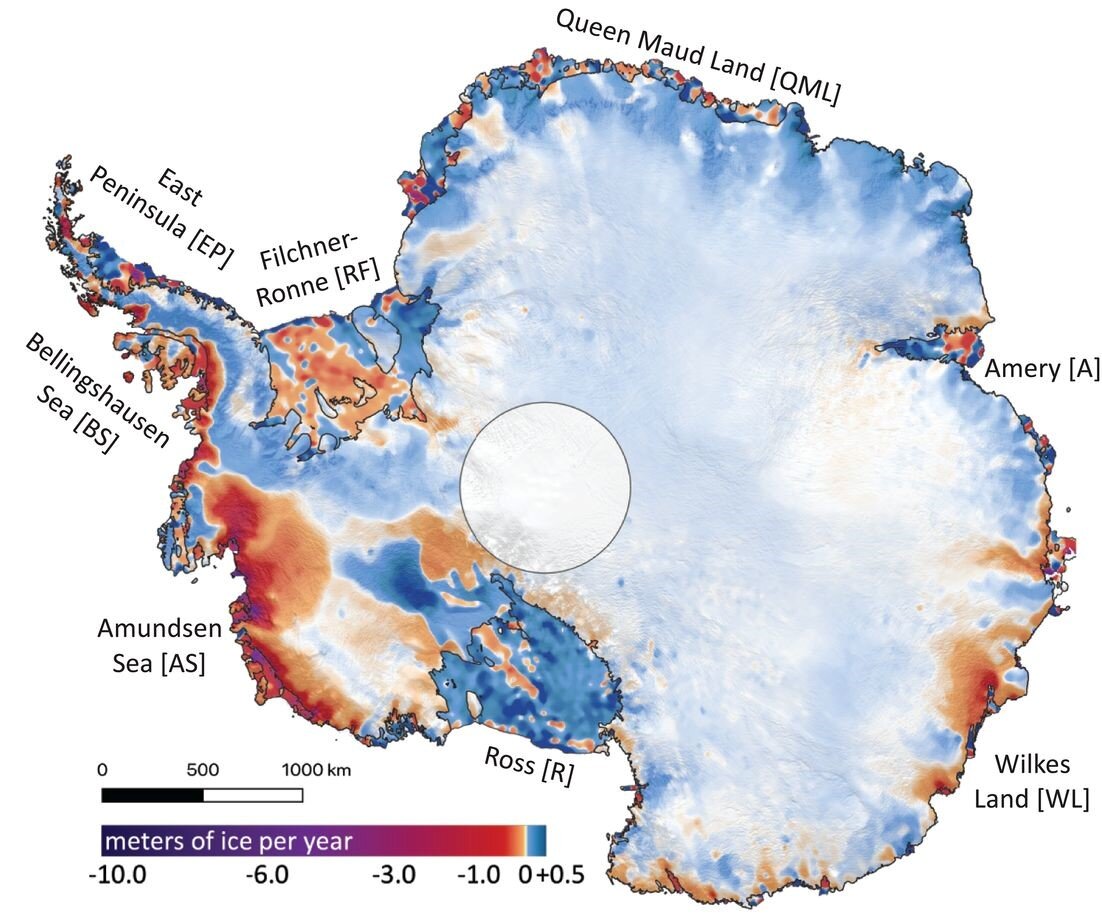

Volcanic CO2 released by the eruptions was supplemented by CO2 produced during combustion of thick, buried coal deposits that lay along the subterranean path of the erupting lava. This stupendous outburst boosted the atmospheric CO2 level from a very low 200 ppm (parts per million) to more than 2,000 ppm, as shown in the next figure.

The conventional wisdom in the past has been that this geologically sudden, gigantic increase in the CO2 level sent the global thermometer soaring – a conclusion sensationalized by mainstream media such as the New York Times. However, that argument ignores the saturation effect for atmospheric CO2, which limits CO2-induced warming to that produced by the first few hundred ppm of the greenhouse gas.

While the composition of the atmosphere 250 million years ago may have been different from today’s, the saturation effect would still have occurred. There’s no question, nevertheless, that end-Permian temperatures were as high as we think, whatever the cause. That’s because the temperatures are based on the highly reliable method of measuring oxygen 18O to 16O isotopic ratios in ancient microfossils.

Such hothouse conditions would have undoubtedly caused the extinction of various species; the severity of the extinction event is revealed by subsequent gaps in the fossil record. Organic carbon accumulated in the deep ocean, depleting oxygen and thus wiping out many marine species such as phytoplankton, brachiopods and reef-building corals. On land, vertebrates such as amphibians and early reptiles, as well as diverse tropical and temperate rainforest flora, disappeared.

All from extreme global warming? Not so fast, says ecologist Jim Steele.

Steele attributes the Permian extinction not to an excess of CO2 at the end of this geological period, but rather to a lack of it during the preceding Carboniferous and the early Permian, as can be seen in the figure above. He explains that all life is dependent on a supply of CO2, and that when its concentration drops below 150 ppm, photosynthesis ceases, and plants and living creatures die.

Steele argues that because of CO2 starvation over this interval, many species had either already become extinct, or were on the verge of extinction, long before the planet heated up so abruptly.

In comparison to other periods, the Permian saw the appearance of very few new species, as illustrated in the following figure. For example, far more new species evolved (and became extinct) during the earlier Ordovician, when CO2 levels were much, much higher but an icehouse climate prevailed.

When CO2 concentrations reached their lowest levels ever in the early Permian, phytoplankton fossils were extremely rare – some 40 million years or so before the later hothouse spike, which is when the conventional narrative claims the species became extinct. And Steele says that 35-47% of marine invertebrate genera went extinct, as well as almost 80% of land vertebrates, from 7 to 17 million years before the mass extinction at the end of the Permian.

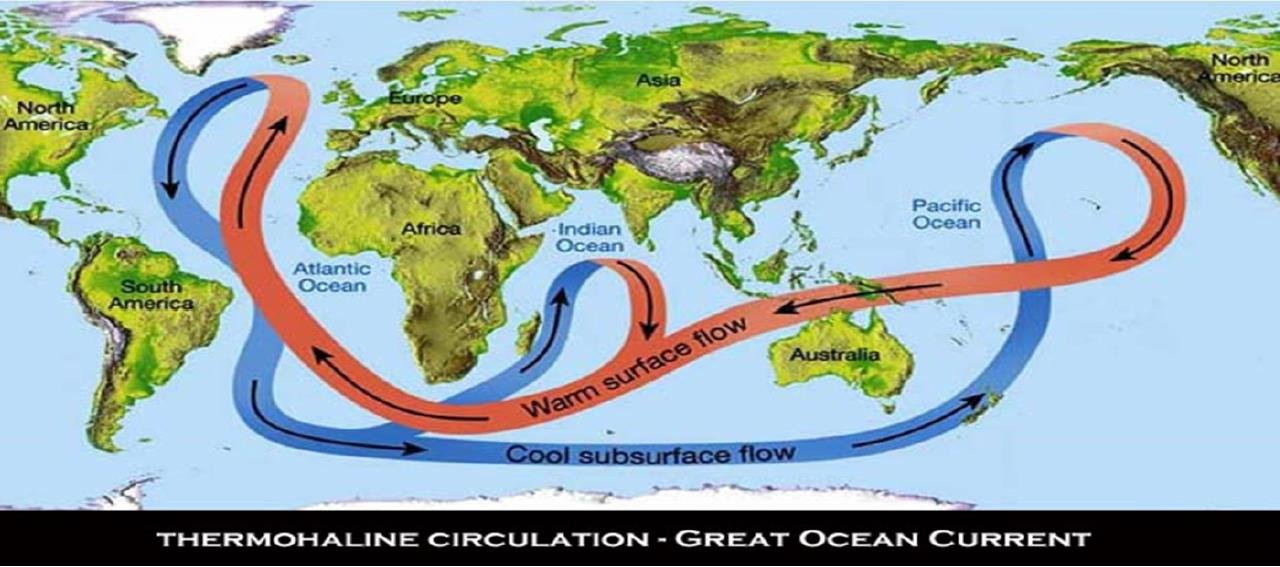

Furthermore, Steele adds, the formation of the supercontinent Pangaea (shown to the left), which occurred during the Carboniferous, had a negative effect on biodiversity. Pangea removed unique niches from its converging island-like microcontinents, again long before the end-Permian.

Next: Unexpected Sea Level Fluctuations Due to Gravity, New Evidence Shows