Ample Evidence Debunks Gloomy Prognosis for World’s Coral Reefs

/According to a just-published research paper, dangers to the world’s coral reefs due to climate change and other stressors have been underestimated and by 2035, the average reef will face environmental conditions unsuitable for survival. This is scientific nonsense, however, as there is an abundance of recent evidence that corals are much more resilient than previously thought and recover quickly from stressful events.

The paper, by a trio of environmental scientists at the University of Hawai‘i, attempts to estimate the year after which various anthropogenic (human-caused) disturbances acting simultaneously will make it impossible for coral reefs to adapt and survive. The disturbances examined are marine heat waves, ocean acidification, storms, land use changes, and pressures from population density such as overfishing, farming runoff and coastal development.

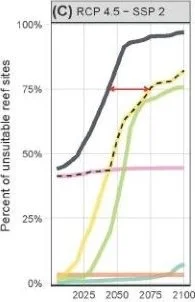

Of these disturbances, the two expected to have the greatest future effect on coral reefs are marine heat waves and ocean acidification, supposedly exacerbated by rising greenhouse gas emissions. The figure to the left shows the scientists’ projected dates of environmental unsuitability for continued existence of the world’s coral reefs, assuming an intermediate CO2 emissions scenario (SSP2). The yellow curve is for marine heat waves, the green curve for ocean acidification.

You can see that the projected unsuitability rises to an incredible 75% by the end of the century for both perturbations, and even surpasses 50% for marine heat waves by 2050. The red arrow indicates the time difference at 75% unsuitability between heat waves considered alone and all disturbances combined (solid black curve).

But these gloomy prognostications are refuted by several recent field studies, two of which I discussed in an earlier blog post. The latest paper, published in May this year, reports on a 10-year study of coral-reef stability on Palmyra Atoll in the remote central Pacific Ocean. The scuba-diving researchers, from California’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography and Saudi Arabia’s King Abdullah University, discovered – by analyzing more than 1,500 digital images – that Palmyra reefs made a remarkable recovery from two major bleaching events in 2009 and 2015.

Bleaching occurs when the multitude of polyps that constitute a coral eject the microscopic algae that normally live inside the polyps and give coral its striking colors. Hotter than normal seawater causes the algae to poison the coral that then expels them, turning the polyps white. The bleaching events studied by the Palmyra researchers were a result of prolonged El Niños in the Pacific.

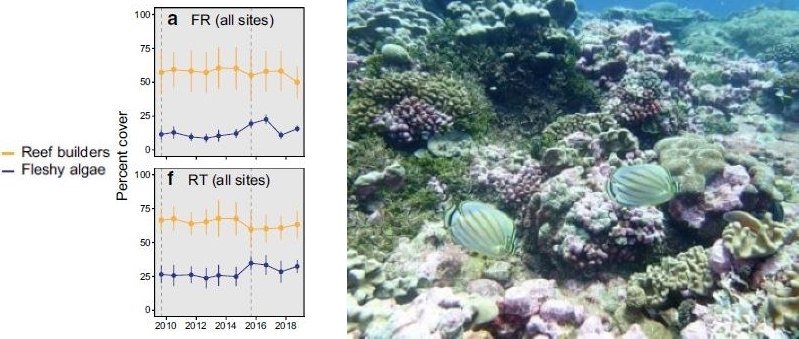

However, the researchers found that, at all eight Palmyra sites investigated, the corals returned to pre-bleaching levels within two years. This was true for corals on both a wave-exposed fore reef and a sheltered reef terrace. Stated Jennifer Smith, one of the paper’s coauthors, “During the warming event of 2015, we saw that up to 90% of the corals on Palmyra bleached but in the year following we saw less than 10% mortality.”

The rapid coral recovery can be seen in the figure on the left below, showing the percentage of coral cover from 2009 to 2019 at all sites combined; FR denotes fore reef, RT reef terrace, and the dashed vertical lines indicate the 2009 and 2015 bleaching events. It’s clear there was only a small change in the reef’s coral and algae populations after a decade, despite the violent disruption of two bleaching episodes. A typical healthy reefscape is shown on the right.

Another 2022 study, discussed in my earlier post, came to much the same conclusions for a massive reef of giant rose-shaped corals hidden off the coast of Tahiti, the largest island in French Polynesia in the South Pacific. The giant corals measure more than 2 meters (6.5 feet) in diameter. Again, the reef survived a mass 2019 bleaching event almost unscathed.

Both these studies were conducted on relatively pristine coral reefs, free from local human stressors such as fishing, pollution, coastal development and tourism. But the same ability of corals to recover from bleaching events has been demonstrated in research on Australia’s famed Great Barrier Reef, many parts of which are subject to such stressors.

Studies in 2021 and 2020 (see here and here) found that both the Great Barrier Reef and coral colonies on reefs around Christmas Island in the Pacific were able to recover quickly from bleaching caused by the 2015-17 El Niño, even while seawater temperatures were still higher than normal. Recovery of the Great Barrier Reef is illustrated in the figure below, showing that the amount of coral on the reef in 2021 and 2022 was at record high levels, in spite of extensive bleaching a few years before.

Apart from making a number of arbitrary and questionable assumptions, the new University of Hawai‘i research is fundamentally flawed because it fails to take into account the ability of corals to rebound from potentially devastating events.

Next: Recent Marine Heat Waves Caused by Undersea Volcanic Eruptions, Not Human CO2