AI Proves Its Mettle in Reconstruction of Antarctic Temperatures

/In a 2025 post, I described the largely unsuccessful attempt of an AI to spearhead research in climate science. Now, however, another AI appears to have succeeded in the more technical task of accurately reconstructing surface air temperatures across Antarctica – something that standard temperature datasets have been unable to achieve. The work is reported in a recent paper by a team of Chinese researchers.

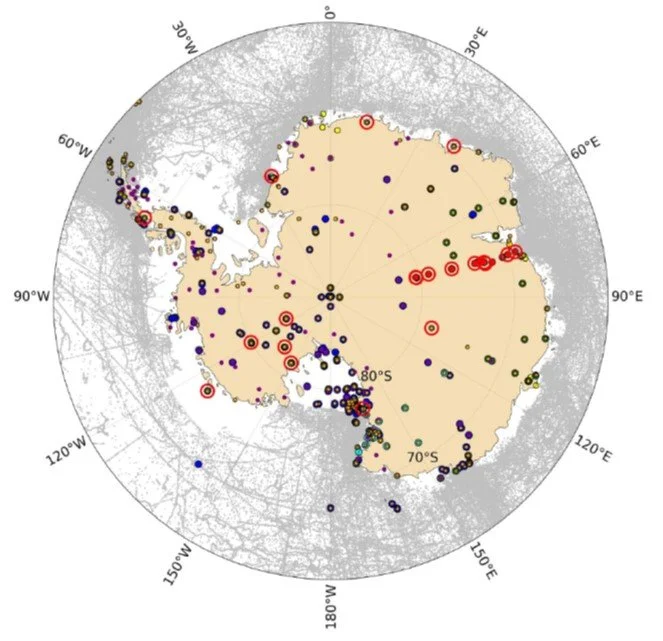

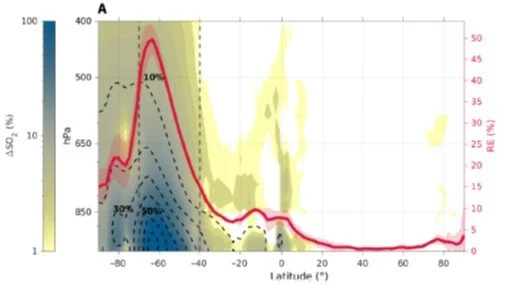

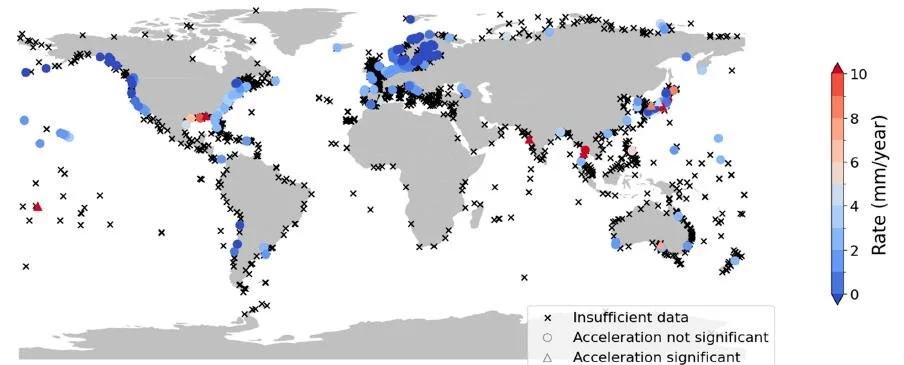

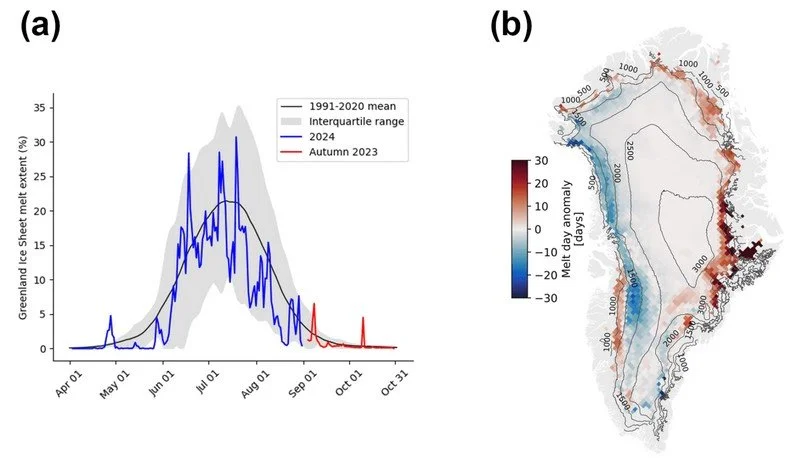

The figure below illustrates the geographical distribution of available observational data in Antarctica from 1979 to 2023. The data comes from a number of manned and automatic weather stations, together with meteorological observations over the ocean collected from ships and buoys. As can be seen, the majority of observations are in coastal or near-coastal regions, precluding full spatial coverage of the continent.

To overcome this shortfall, the limited station observations have traditionally been interpolated using various reanalyses. But it’s difficult for reanalysis datasets to capture complex spatial patterns, say the researchers, and such datasets often contain significant uncertainties. Moreover, deriving surface air temperatures from reanalysis datasets depends in part on model simulations rather than actual instrumental measurements.

In the light of these limitations to an accurate reconstruction of Antarctic temperatures, the Chinese research team has applied deep learning methods. This approach has already been utilized successfully to reconstruct Arctic temperatures.

Antarctic temperatures were reconstructed using daily surface air temperature data from the various sources depicted in the figure above. Daily average temperatures were calculated from observations made at 3-hour intervals for some sources, 1-hour intervals for others. Training data for the deep learning model was provided by surface air temperatures from the three reanalysis datasets that showed the best agreement with observed temperatures.

The training data, which covered the period from 1979 to 2005, totaled 29,211 daily temperature samples. Using reanalysis data from different time periods, such as 1995 to 2021, as the training set had little impact on the temperature reconstruction. Validation of the training data and testing of the reconstructed temperature set employed reanalysis data from 2006 to 2012 and 2013 to 2018, respectively.

Testing of the reconstructed Antarctic temperatures was conducted for three specific days in 2015: January 1, July 1 and November 1. For these days, the reconstructed temperatures were found to be highly correlated with their reanalysis counterparts, with spatial correlation coefficients >0.99. The researchers say this correlation shows that the trained deep learning model is capable of accurately reproducing Antarctic surface air temperatures, even with the limited observational data available.

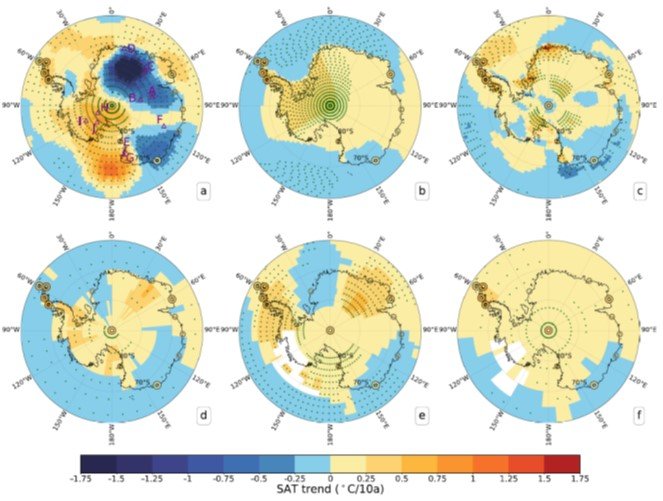

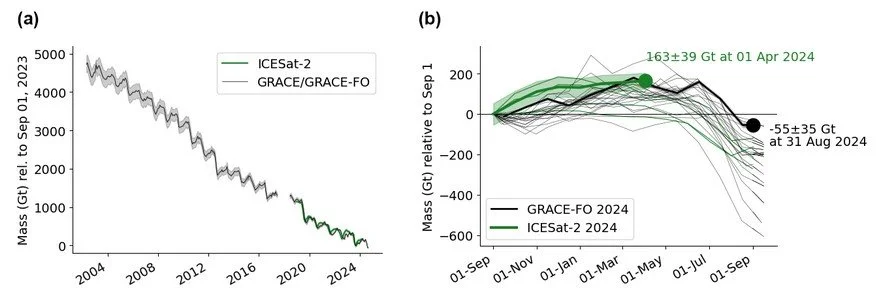

Just how different the reconstructed surface temperatures are from global observational temperature datasets for Antarctica is depicted in the next figure. The figure shows linear trends in annual Antarctic surface air temperatures from 1979 to 2023, measured in degrees Celsius per decade. The datasets are: (a) this reconstruction; (b) Berkeley Earth; (c) ERA reanalysis; (d) NOAAGlobalTemp5.1; (e) GISTEMPv4; and (f) HadCRUT5.

You can see that none of the standard datasets exhibit the pronounced cooling trend in East Antarctica in (a), something that was inferred earlier from the ERA reanalysis dataset by a different group of Chinese researchers. Nevertheless, all datasets show warming in the Antarctic Peninsula (on the left of the continent in the maps above).

Differing from the annual trends is the pattern for the summer months (November to April) only, presented in the figure below for the period from 1989 to 2022. Although the cooling trend still dominates in East Antarctica, warming is no longer prominent in the Peninsula but is found in West Antarctica and the southern portion of East Antarctica.

East Antarctica actually experienced a summer heat wave in 2022, when the temperature soared to -10.1 degrees Celsius (13.8 degrees Fahrenheit) at the Concordia weather station, located at the 4 o’clock position from the South Pole, on March 18. This balmy reading was the highest recorded hourly temperature at that station since its establishment in 1996, and 20 degrees Celsius (36 degrees Fahrenheit) above the previous March record high there. Remarkably, the temperature remained above that record for three consecutive days, including nighttime.

But Antarctica is nothing if not unpredictable. Despite the 2022 heat wave, the mercury dropped to -51.2 degrees Celsius (-60.2 degrees Fahrenheit) on January 31, 2023. This marked the lowest January temperature recorded anywhere in Antarctica since the first meteorological observations there in 1956. Two days earlier on January 29, the nearby Vostok station, about 400 km (250) miles closer to the South Pole, registered a low temperature of -48.7 degrees Celsius (-55.7 degrees Fahrenheit), that location’s lowest January temperature since 1957.

Such swings from record highs to record lows remain a puzzle, but the present reconstruction at least helps to characterize long-term trends.

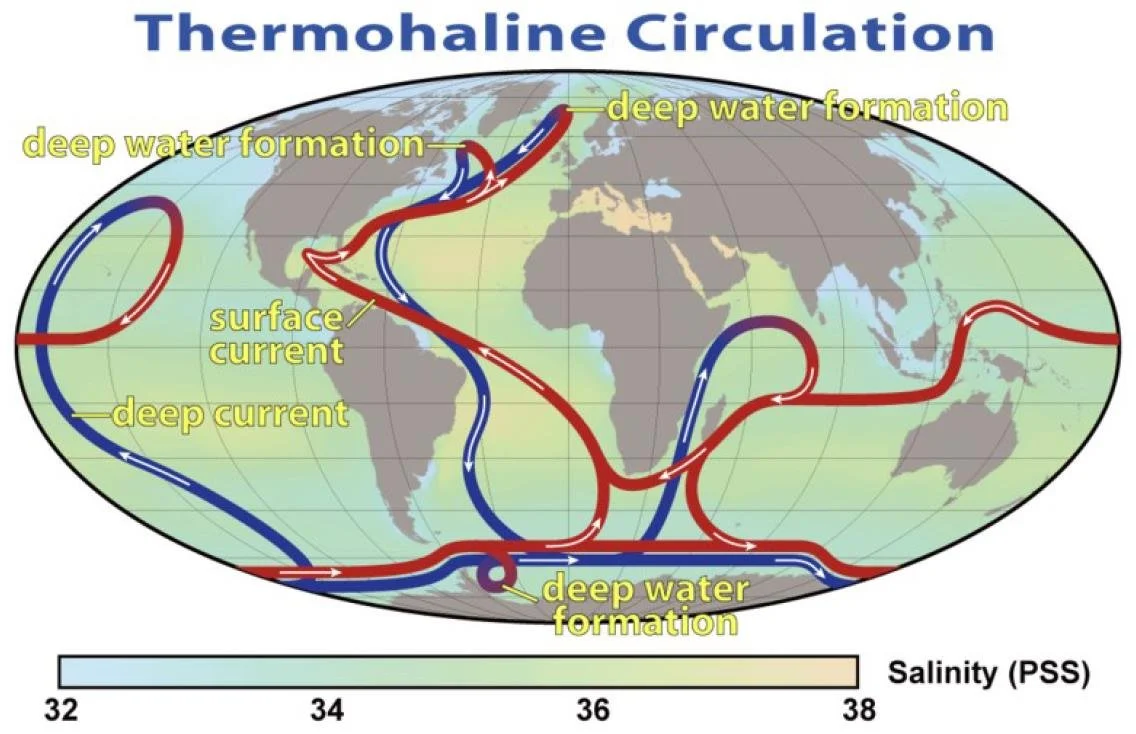

Next: The Atlantic “Cold Blob” – Cause for Alarm or Just a Curiosity?