How Hype Is Hurting Science

/The recent riots in France over a proposed carbon tax, aimed at supposedly combating climate change, were a direct result of blatant exaggeration in climate science for political purposes. It’s no coincidence that the decision to move forward with the tax came soon after an October report from the UN’s IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), claiming that drastic measures to curtail climate change are necessary by 2030 in order to avoid catastrophe. President Emmanuel Macron bought into the hype, only to see his people rise up against him.

Exaggeration has a long history in modern science. In 1977, the select U.S. Senate committee drafting new low-fat dietary recommendations wildly exaggerated its message by declaring that excessive fat or sugar in the diet was as much of a health threat as smoking, even though a reasoned examination of the evidence revealed that wasn’t true.

About a decade later, the same hype infiltrated the burgeoning field of climate science. At another Senate committee hearing, astrophysicist James Hansen, who was then head of GISS (NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies), declared he was 99% certain that the 0.4 degrees Celsius (0.7 degrees Fahrenheit) of global warming from 1958 to 1987 was caused primarily by the buildup of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, and wasn’t a natural variation. This assertion was based on a computer model of the earth’s climate system.

At a previous hearing, Hansen had presented climate model predictions of U.S. temperatures 30 years in the future that were three times higher than they turned out to be. This gross exaggeration makes a mockery of his subsequent claim that the warming from 1958 to 1987 was all man-made. His stretching of the truth stands in stark contrast to the caution and understatement of traditional science.

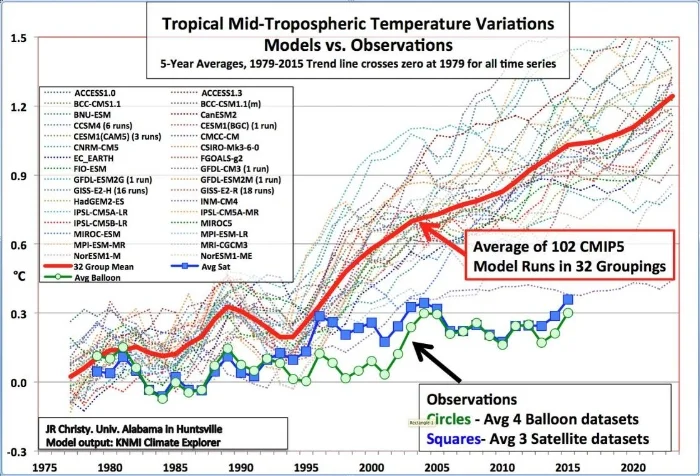

But Hansen’s hype only set the stage for others. Similar computer models have also exaggerated the magnitude of more recent global warming, failing to predict the pause in warming from the late 1990s to about 2014. During this interval, the warming rate dropped to below half the rate measured from the early 1970s to 1998. Again, the models overestimated the warming rate by two or three times.

An exaggeration mindlessly repeated by politicians and the mainstream media is the supposed 97% consensus among climate scientists that global warming is largely man-made. The 97% number comes primarily from a study of approximately 12,000 abstracts of research papers on climate science over a 20-year period. But what is never revealed is that almost 8,000 of the abstracts expressed no opinion at all on anthropogenic (human-caused) warming. When that and a subsidiary survey are taken into account, the climate scientist consensus percentage falls to between 33% and 63% only. So much for an overwhelming majority!

A further over-hyped assertion about climate change is that the polar bear population at the North Pole is shrinking because of diminishing sea ice in the Arctic, and that the bears are facing extinction. For global warming alarmists, this claim has become a cause célèbre. Yet, despite numerous articles in the media and photos of apparently starving bears, current evidence shows that the polar bear population has actually been steady for the whole period that the ice has been decreasing – and may even be growing, according to the native Inuit.

It’s not just climate data that’s exaggerated (and sometimes distorted) by political activists. Apart from the historical example in nutritional science cited above, the same trend can be found in areas as diverse as the vaccination debate and the science of GMO foods.

Exaggeration is a common, if frowned-upon marketing tool in the commercial world: hype helps draw attention in the short term. But its use for the same purpose in science only tarnishes the discipline. And, just as exaggeration eventually turns off commercial customers interested in a product, so too does it make the general public wary if not downright suspicious of scientific proclamations. The French public has recognized this on climate change.