Antarctica Sending Mixed Climate Messages

/Antarctica, the earth’s coldest and least-populated continent, is an enigma when it comes to global warming.

While the huge Antarctic ice sheet is known to be shedding ice around its edges, it may be growing in East Antarctica. Antarctic sea ice, after expanding slightly for at least 37 years, took a tumble in 2017 and reached a record low in 2023. And recent Antarctic temperatures have swung from record highs to record lows. No one is sure what’s going on.

The influence of global warming on Antarctica’s temperatures is uncertain. A 2021 study concluded that both East Antarctica and West Antarctica have cooled since the beginning of the satellite era in 1979, at rates of 0.70 degrees Celsius (1.3 degrees Fahrenheit) per decade and 0.42 degrees Celsius (0.76 degrees Fahrenheit) per decade, respectively. But over the same period, the Antarctic Peninsula (on the left in the adjacent figure) has warmed at a rate of 0.18 degrees Celsius (0.32 degrees Fahrenheit) per decade.

During the southern summer, two locations in East Antarctica recorded record low temperatures early this year. At the Concordia weather station, located at the 4 o’clock position from the South Pole, the mercury dropped to -51.2 degrees Celsius (-60.2 degrees Fahrenheit) on January 31, 2023. This marked the lowest January temperature recorded anywhere in Antarctica since the first meteorological observations there in 1956.

Two days earlier on January 29, 2023, the nearby Vostok station, about 400 km (250) miles closer to the South Pole, registered a low temperature of -48.7 degrees Celsius (-55.7 degrees Fahrenheit), that location’s lowest January temperature since 1957. Vostok has the distinction of reporting the lowest temperature ever recorded in Antarctica, and also the world record low, of -89.2 degrees Celsius (-128.6 degrees Fahrenheit) on July 21, 1984.

Barely a year before, however, East Antarctica had experienced a heat wave, when the temperature soared to -10.1 degrees Celsius (13.8 degrees Fahrenheit) at the Concordia station on March 18, 2022. This balmy reading was the highest recorded hourly temperature at that weather station since its establishment in 1996, and 20 degrees Celsius (36 degrees Fahrenheit) above the previous March record high there. Remarkably, the temperature remained above the previous March record for three consecutive days, including nighttime.

Antarctic sea ice largely disappears during the southern summer and reaches its maximum extent in September, at the end of winter. The two figures below illustrate the winter maximum extent in 2023 (left) and the monthly variation of Antarctic sea ice extent this year from its March minimum to the September maximum (right).

The black curve on the right depicts the median extent from 1981 to 2010, while the dashed red and blue curves represent 2022 and 2023, respectively. It's clear that Antarctic sea ice in 2023 has lagged the median and even 2022 by a wide margin throughout the year. The decline in summer sea ice extent has now persisted for six years, as seen in the following figure which shows the average monthly extent since satellite measurements began, as an anomaly from the median value.

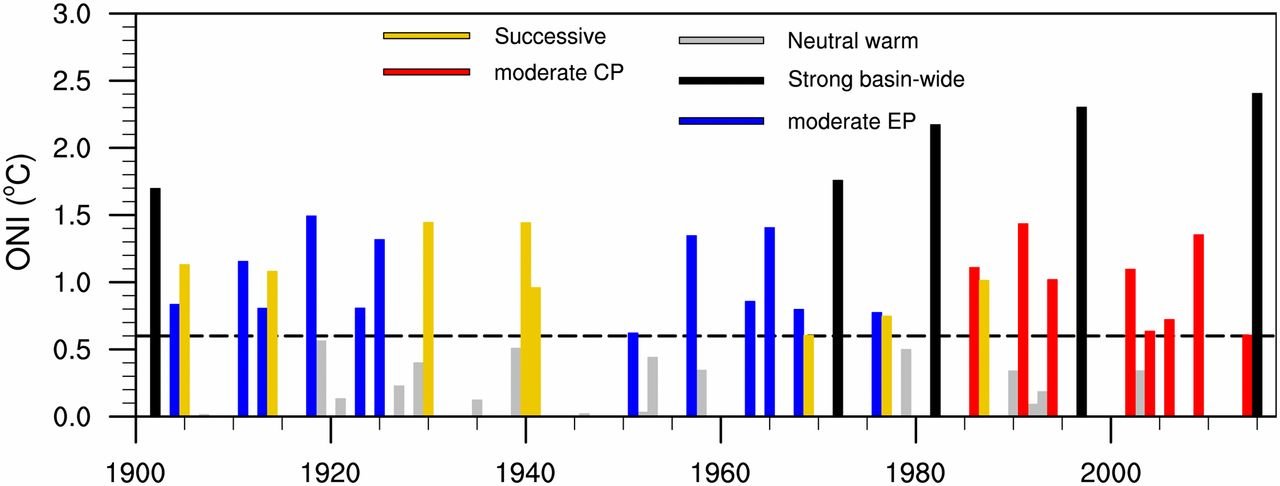

The overall trend from 1979 to 2023 is an insignificant 0.1% per decade relative to the 1981 to 2010 median. Yet a prolonged increase above the median occurred from 2008 to 2017, followed by the six-year decline since then. The current downward trend has sparked much debate and several possible reasons have been put forward, not all of which are linked to global warming. One analysis attributes the big losses of sea ice in 2017 and 2023 to extra strong El Niños.

Melting of the Antarctic ice sheet is currently causing sea levels to rise by 0.4 mm (16 thousandths of an inch) per year, contributing about 10% of the global total. But the ice loss is not uniform across the continent, as seen in the next figure showing changes in Antarctic ice sheet mass since 2002.

In the image on the right, light blue shades indicate ice gain while orange and red shades indicate ice loss. White denotes areas where there has been very little or no change in ice mass since 2002; gray areas are floating ice shelves whose mass change is not measured by this satellite method.

You can see that East Antarctica has experienced modest amounts of ice gain, which is due to warming-enhanced snowfall. Nevertheless, this gain has been offset by significant loss of ice in West Antarctica over the same period, largely from melting of glaciers – which is partly caused by active volcanoes underneath the continent. While the ice sheet mass declined at a fairly constant rate of 133 gigatonnes (147 gigatons) per year from 2002 to 2020, it appears that the total mass may have reached a minimum and is now on the rise again.

Despite the hullabaloo about its melting ice sheet and shrinking sea ice, what happens next in Antarctica continues to be a scientific mystery.

Next: Two Statistical Studies Attempt to Cast Doubt on the CO2 Narrative